Notes On "I Don't Want to Live on the Moon"

What Sesame Street Taught Me About Colonizing Space

Six billion kilometers from Earth, Voyager 1 looks back and takes a photograph. Earth is less than a pixel in size from that distance and astronomer Carl Sagan compared it to a speck of dust floating in a sunbeam, calling the picture “Pale Blue Dot.” The snapshot is part of a series used to create a “Family Portrait” of the Solar System, a composite of sixty frames, but “Pale Blue Dot” became an enduring image on its own. If the viewer does not know what they are looking at, the photo means nothing, but if they know that the pixel is the planet on which they will live and die—what does such distance inspire?

On that dot, it is 1990 and I am three years old, watching a VHS tape of Sesame Street. A plush Ernie doll sits on the couch beside me, while on the television Ernie sits on the Moon, singing about imaginary adventures. A dull ache that I will later associate with nostalgia tugs on my heart as Ernie looks back at the Earth and concludes that he does not want to live on the Moon because he would miss Sesame Street too much. I also understand the gravitational pull of home.

Ernie’s song, “I Don’t Want to Live on the Moon,” was composed by Jeff Moss in 1978, but made its first appearance on Sesame Street in 1984 and was a mainstay of Children’s Television Workshop compilations and albums for years afterward. Awake in the middle of the night, but still dreaming, Ernie imagines traveling to the Moon, swimming under the sea, visiting the jungle, and traveling back in time. Although each of these adventures would be fun, he does not wish to stay in any of these “strange places” permanently.

In other verses of the song, Ernie describes himself encountering animals—fish, lions, even a dinosaur—but when he sings about visiting the Moon, he has no other creatures with whom to engage. Ernie focuses back on Earth instead, and when he sings that he would “miss all the places and people he loves,” I know that he means Bert and his cozy apartment. I also know that I would miss my cat, my family, and my bedroom on a quiet street from which I can see the stars, too.

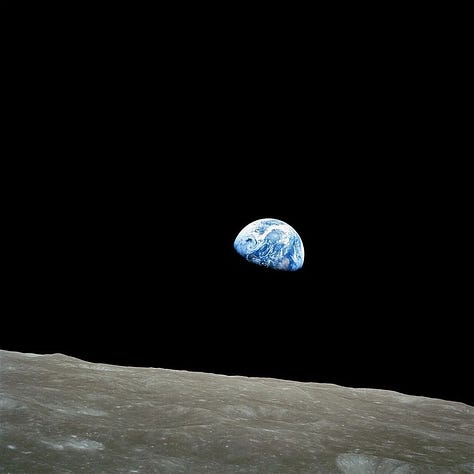

In the video for “I Don’t Want to Live on the Moon,” Ernie sits side-saddle in the curve of the Moon and leans back to rest, as though to dream about Earth, visible as a glowing orb in the bottom right corner of the frame. Whereas the image of Ernie on a crescent represents fantasy, depicting a phase of the Moon as it would appear from Earth or in a child’s imagination, Earth seems drawn from life, specifically from the two photos of our planet published in the years before Ernie’s dream.

On December 24, 1968, taking photos of the Moon’s surface while in lunar orbit on NASA’s Apollo 8 mission, William Anders looked out the window behind him and saw Earth. He took both black and white and color photos of the view, called “Earthrise.” Compared to the barren, colorless moon, Earth appears strikingly vivid and luminescent. Nature photographer Galen Rowell called “Earthrise” “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken.” On the 50th anniversary of the photo, William Anders reflected, “We set out to explore the moon and instead discovered the Earth.”

The “Blue Marble” photo was taken en route to the moon by the crew of Apollo 17 in December 1972. “Blue Marble” was released as the Environmental Movement grew in the United States, and whereas work such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) investigated specific environmental harms, this photo of Earth created a stirring, literal big picture. Since Apollo 17, no human has left Earth’s orbit or seen the whole of our planet from above—except for Ernie.

As a lonely, sensitive child, the kind who worried about hurting her teddy bear’s feelings and never quite fit in, I felt sad while listening to Ernie’s song for reasons that I still struggle to identify. The slow pace and the plaintive notes of the flute paired with Ernie’s wistful vocals evoke a feeling adjacent to homesickness. The emotion resembles how images of Earth taken from lunar orbit made people feel upon their release. The uncanniness of seeing the globe from such a distance emphasized the smallness of individual humans, but also the miracle of our planet. We are on that Blue Marble, floating in the incomprehensible vastness of space. This planet is our only home.

Well, I'd like to visit the moon

On a rocketship high in the air

Yes, I'd like to visit the moon

But I don't think I'd like to live there

In the environmentalist circles I spend time in, “There’s No Planet B” has become a cliche, but no less true. With the priorities and power of billionaires laid bare in the recent U.S. election, it seems clear that, although we have solutions to help fight climate change and clean up our ecosystems, political will and capital are being spent elsewhere. And there are those who would rather pursue commercial space flight or setting up colonies on Mars.

Recently, Zach Weinersmith, co-author of A City on Mars, told Regina Barber of NPR's Short Wave:

“Elon Musk might want to put on a cowboy hat and fly off to Mars and start his Martian city and leave this polluted planet behind to its wars and devastation and if he thinks that, he is a fool, because Mars is so bad, you could not for $10 trillion make Earth as bad as Mars…So we have to make it work here.”

Maybe we could live on Mars, but would it be worth it? And, if a select few left Earth behind for Mars, what about the rest of us?

The risks of these operations were also demonstrated when a malfunctioning Boeing Starliner stranded two NASA astronauts, Sunita Williams and Barry Wilmore, on the International Space Station for an additional eight months. On June 5th, 2024, they left for a mission that was supposed to last for eight days, but after the Boeing Starliner carrying them began to leak helium and experienced thruster malfunctions, their return was pushed until they can return on a SpaceX Crew Dragon flight back to Earth in February 2025. They are part of a record-making group of 19 humans living and working in space. Away, but still part of the community.

"I didn’t understand that once I got there, I’d actually feel just as close to Earth. And so it turns out that home is bigger than we thought," retired NASA astronaut Cady Coleman told Sean Rameswaram at Vox. She felt jealous of those additional months at the International Space Station, explaining that space is like a big science lab, in which the variable of gravity is removed from all the experiments:

"It’s a magical place. And I think what’s really meaningful is knowing that everything that you do up there matters. It gets us one step closer to going back to the moon and going to Mars.”

I do not doubt that working in space unveils wonders I cannot imagine, but I also feel like splitting hairs, asking if everything we do down here doesn’t matter too. My mind drifts to Sesame Street and the lessons I learned there about life on Earth.

Though I'd like to look down at the Earth from above

I would miss all the places and people I love

So although I might like it for one afternoon

I don't wanna live on the moon

My daughter is three years old and likes to pretend that she and her father are Bert and Ernie. We listen to “I Don’t Want to Live on the Moon” and the song carries a different implication in an era marked by anxiety over the climate and the future of human life on Earth. I feel sad sometimes, as if from nowhere, when I enjoy sunlight filtering through the leaves of my tropical houseplants, observe squash bees in my pumpkin patch, or watch bats fly out of our neighbor’s giant Blue Spruce trees. The beauty of these minutiae evokes an ache of love and fear of great loss.

Both NASA and commercial space companies have goals to travel beyond our moon, to Mars. NASA’s upcoming Artemis missions will focus on developing skills and resource management strategies for extended stays, as a method to research and prepare for missions to Mars by the 2030s. Boeing and Space X are both part of a multi-billion dollar effort to develop commercial spaceflights both for capital gains and to shuttle NASA’s astronauts to and from the International Space Station. NASA granted Boeing a $4.2 billion dollar contract and over $2 billion in contracts to SpaceX. SpaceX has been more successful than Boeing so far, transporting astronauts to the ISS twenty times, but the company also saw a Falcon 9 rocket explode on the launchpad in 2016. Commercial spaceflight companies also hope to reach Mars by the late 2020s, and in the meantime offer the chance for laypeople to travel to space—at a steep cost.

Blue Origin CEO Jeff Bezos, Space X CEO Elon Musk, and Virgin Galactic CEO Richard Branson have each begun launching space travel companies. Individuals who have visited the International Space Station through Axiom Space paid $55 million each for an eight-night trip. The opportunity to fly on Virgin Galactic's spaceplane costs $450,000. That's not to mention the environmental costs for the rest of us. For example, Blue Origin’s test launches emitted enough methane that the pollution could be seen from space. It is not necessarily a zero-sum game, but public opinion polls about these ventures indicate that majorities would rather see billionaires devote their wealth and energy to helping solve problems here on Earth—hunger, poverty, climate change—than to exploring space. If a Muppet can just imagine looking down on Earth and realize that everything he loves is here at home, why are these humans seemingly immune from such introspection? Did they never watch Sesame Street?

So, if I should visit the moon

Well, I'll dance on a moonbeam and then

I will make a wish on a star

And I'll wish I was home once again

William Shatner, the oldest person to travel to space as of this writing, orbited Earth in Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin space shuttle in October 2021. Initially, Shatner enthusiastically promoted the flight, anticipating unparalleled adventure. When he looked out into the depths of space, however, Shatner was surprised to find not wonder, but gripping sadness. He saw death. Turning “back toward the light of home,” he felt more drawn to what he had left behind than by the frontier outside the rocket’s windows. In his book, Boldly Go: Reflections on a Life of Awe and Wonder, Shatner explains, “I discovered that the beauty isn’t out there, it’s down here, with all of us. Leaving that behind made my connection to our tiny planet even more profound.”

Shatner himself explains his feeling as the Overview Effect, a term coined by Frank White in his 1987 book, The Overview Effect—Space Exploration and Human Evolution. After many interviews with astronauts, White described a common sentiment from their space travel experiences. The view of Earth from beyond its boundaries generated feelings ranging from the sublime to sadness, united by an epiphany of how precious, fragile, and beautiful our planet is. Transcending Earth’s orbit ultimately made astronauts feel more bound to it.

Public response to the “Earthrise” and “Blue Marble” photos, some of the most reproduced images in history, can also explain why, even in Indiana in the 1990s—hardly a bastion of progressive thought—I was in a primary school musical about environmentalism: Every Day Is Earth Day. White argues that images of Earth from space produce a mild version of the Overview Effect—not nearly as intense as what astronauts feel, but strong enough to jolt the viewer into a state of awe. He asserts that the Overview Effect has been used to deploy the “whole Earth” as a symbol in movements devoted to both ecology and peace:

If the idea of the Overview Effect as a message is correct, it should be possible to see the overview experience being disseminated in support of a more peaceful, self-aware, and ecologically careful species. For example, many astronauts return from space with an intense interest in ecology. From space, it is easy for them to see the interdependence of Earth's environment and the cost to humanity if anything is done to make the planet unlivable.

Writing in the year when I was born, White floats that word— “unlivable”—as a hypothetical. When I read it back 37 years later, it bursts from the page like an asteroid.

Though I'd like to look down at the Earth from above

I would miss all the places and people I love

So although I may go, I'll be coming home soon

'Cause I don't want to live on the moon

In September 2025, Artemis II is slated to take the first crew of American astronauts to the Moon’s orbit since Apollo 17. Simultaneously, China, Russia, and India are also working on missions to the Moon, exemplifying a new era of space travel and exploration, and perhaps a new space race. Aboard NASA’s Orion spacecraft, scientists intend to take an important step in a mission to establish a long-term presence on the Moon. In 2026, NASA plans to send humans back to the lunar surface aboard Artemis III. They will add their footprints to those left by crews from the Apollo Era, still visible in the absence of weather or wind to smooth them away. These astronauts will step on the Moon in a time of intense scrutiny over lasting human impacts on the natural world, of which we are part. In their plan to build a base on the Moon for exploration into deep space, they are sure to leave more than footprints.

In the meantime, Suni Williams and Barry Wilmore are still in space, where they will celebrate the holidays and the New Year, dates on the calendar they had meant to spend here on Earth. When they return and debrief the rest of us about their extra months out there, what will they have learned about life on Earth? How will they feel about the journey and the return to the people and places they love?

No, I don't

Want to live

On the moon

Wow. I can honestly say this has been such a thought-provoking piece. I've never thought long and hard about all of these things, and you make so much sense. I wonder if it could work for an opinion piece when those two astronauts do land.

Right on, sister... the entirety of the manned-mission space "exploration" is misguided, and is a terrible waste of money. The space station is a megalomaniacal enterprise akin to the building of pyramids in ancient Egypt or the moai statues on Easter Island. We now put pyramids in orbit—how ridiculous is that?! The only way to do space exploration is with unmanned missions, and there have already been so many successful ones.