Create a Wonder Habit

Making space for awe and how it benefits your body and mind

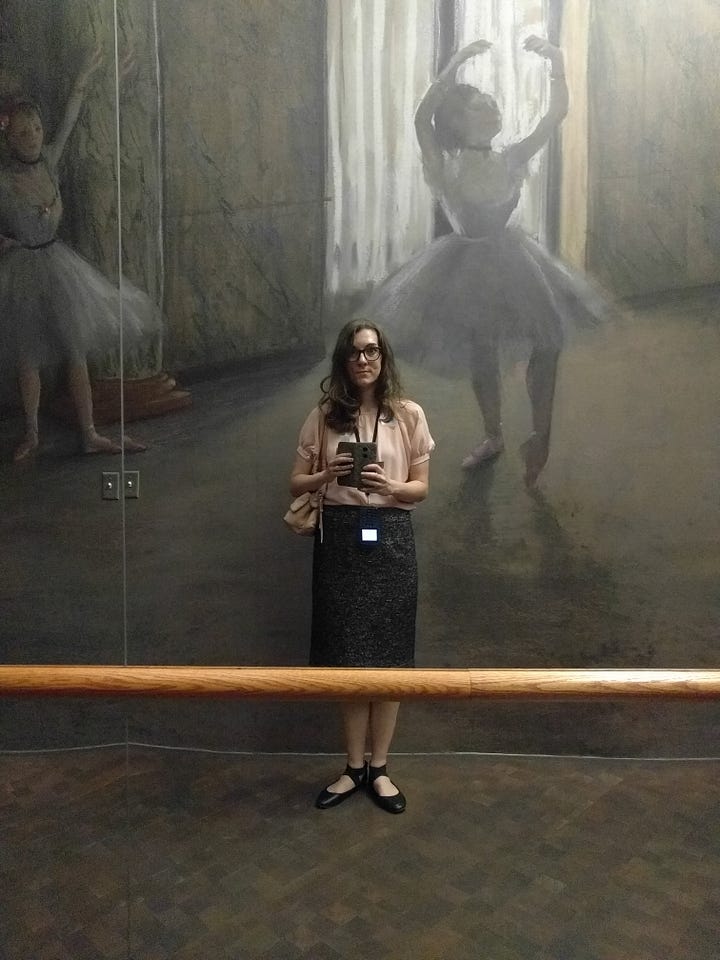

There’s a painting at the Denver Art Museum that I go out of my way to see. The Family of Street Acrobats: the Injured Child (La Famille du Saltimbanque: L’Enfant Blessé) by Gustave Doré, French (1832-1883) pulls me in for reasons I can’t quite pinpoint. The facial expressions, the blueness, maybe?

Last spring, I was chatting with our daughter’s teacher about a visit to the museum, and she said, “You know, my favorite painting in the whole museum is of these circus performers…”

“The blue one!?” I said. Oh, my delight carried me through days.

Art provides so many opportunities to connect with other people and to discover things we’ve hidden inside ourselves.

Of course, nature can do so as well.

Mushrooms sprouted in the yard after an especially wet spring. Normally, our area is dry and drought-prone, so to have a patch of mushrooms spring up in our garden felt like a marvel, especially to my three-year-old daughter.

She lay on the grass for an hour, looking at the mushrooms, examining their gills. She plucked one and brought it to me, inviting me into her moment of awe.

I often call up this memory; it’s a kind of happy place for me, and it reminds me of moments when I have been similarly moved by simple beauty. It’s my field of daffodils, so to speak.

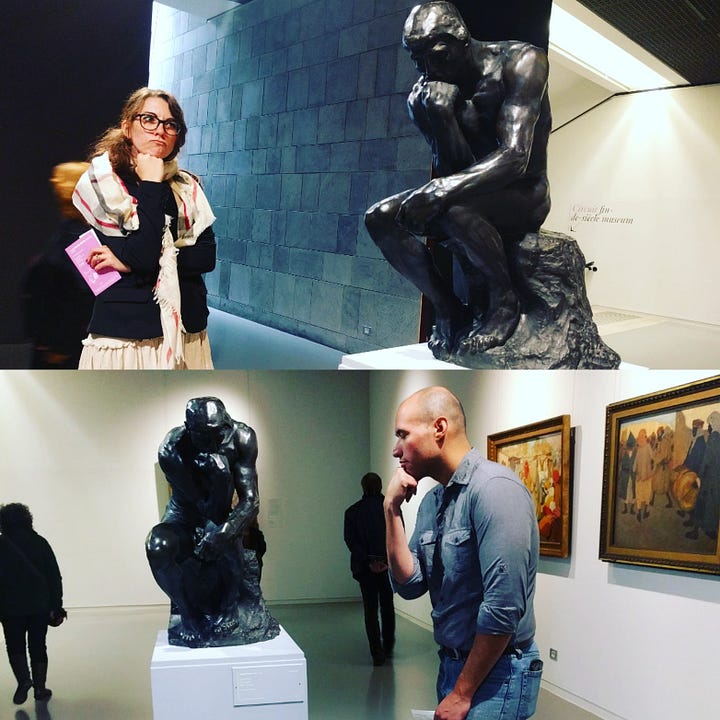

The Link Between Wonder and Wellness

Recently, The Washington Post published an article (by Dana Milbank, Dec 19) about “Finding Awe” tours at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. The tours were started by Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at UC Berkeley and author of Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life. The tours draw on research that demonstrates how viewing art, even if you “don’t get it,” can have meaningful benefits.

But these benefits are not just available in museums. According to Keltner, “Simply slowing down to take in the simple beauties around us is an antidote to the moral ugliness of our attention-captured, online life, and visual art and the spaces of such contemplation a gym for such training.”

Ketlner’s work is part of a growing body of evidence that experiencing wonder and awe benefits mental and physical well-being.

As Paul Wright, M.D., explains, when we experience wonder or awe—through art or otherwise—several important areas of our brains are engaged. The prefrontal cortex, which controls executive function, lights up, as does the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the region that helps with emotional regulation. Our brains release dopamine and endorphins, and our cortisol levels begin to drop.

A 2021 study found that people who self-reported more experiences of awe had lower markers of inflammation in their bodies and were more satisfied with their lives. Other research indicates that, in addition to being good for mental and emotional wellness, the effects of awe on inflammation and stress hormones also benefit cardiovascular health.

Furthermore, wonder might make us better people. Sean Goldy, a postdoctoral research fellow at Johns Hopkins, says that experiences that help us put ourselves in the context of something bigger (a hallmark of awe) “opens people up to things outside themselves and makes them more attuned to others.”

These feelings can lead to greater curiosity, tolerance, and prosocial behavior.

There’s debate about whether or not art and literature really help people build empathy, but these findings would seem to offer a clue.

Do Not Reserve Awe for Grand Moments

If you’ll allow me to put my dusty English professor hat back on for a moment, I want to take us back to the Romantics. Watching Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein reminded me of when I taught the novel and the difficulty I had getting my students to connect with some of its themes, particularly the Sublime. (Tate Modern has a wonderful page exploring “art of the sublime.”)

For the Romantics, British poets and artists active from 1785 to 1832, the Sublime was an aesthetic that expressed the awe, terror, or overwhelming feelings stirred by being in the vastness of nature, such as in a storm, on a cliff, or at sea. In Frankenstein, both Victor and his Creature experience the Sublime while trekking across the Alps or a frozen sea, trying to kill each other. Those of us who have traversed forests or gone to the seaside or stood on a mountaintop likely have memories of intense wonder at the natural world that, in its massive beauty, reminds us of how small we are. Yet, I was teaching this concept to 18-year-olds in a small town in the middle of a cornfield. I needed a more accessible image to resonate with them.

Fortunately, William Wadsworth gave us an essential Sublime poem that does not deal with nature’s might and majesty, but instead presents the spiritual feeling of connecting with the natural world through a field of daffodils. You probably read “I Wandered Lonely As a Cloud” in school at some point. It begins:

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

It’s simple. Pastoral. Almost placeless. He was in the English countryside, but if you sub in a different flower for daffodils, he could be in Ohio, or Holland, or the cow pasture down the road from me when the alfalfa blooms.

Wadsworth compares the flowers, moved by a breeze, to stars in the sky and waves on the sea, connecting their mundane beauty to grander natural phenomena, and then he concludes by expressing how the daffodils continue to bring him joy and peace long after he walks away:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

Now, the idea of a poet being moved by a field of flowers is a cliche. But, here’s my hot-take: when everything feels hard and tenuous and heightened, we need that g-d whimsy and sentimentality to ground ourselves. I don’t like schlocky art, but in our day-to-day lives, those simple moments of wonder help us survive, connect with each other and the world beneath our feet, and remind us of the better parts of being a person.

How to Build Moments of Wonder into Every Day

I am literally telling you to smell the flowers. We are in a very jaded cultural moment, and I think it makes sense that in response, people are leaning into analog (more on that next week), whimsical, earthy practices. If you want to feel grand moments of awe and wonder, I encourage that. Go forth and climb those mountains, or patronize a local art gallery, or travel. Go! Most of us can’t do that all the time, though, so here are some ways to get into a habit of experiencing smaller moments of wonder regularly:

Go for a walk with the intention of finding something beautiful. Sometimes we go for walks to clear our heads or to think about something we’re stuck on, but try going for the simple purpose of finding a beautiful bird, a tree, the first flowers of spring, a neighbor’s garden, etc. Take notice.

Look closer. As you go about your ordinary day, practice looking for things that are interesting or beautiful. If something tugs at your attention, look closer. Notice details. Watch other creatures going about their business. Observe the parts of a flower. Often, the closer you look at a natural object (or a work of art!), the more interesting and wonder-ful it becomes to you. This is a lesson I have learned time and again as a beekeeper.

Become an “expert” on something small. Is there something you’re curious about? Make a little time each day to learn more about, for example, mushrooms, or wildflowers that grow in your region, or how bread is made, or birds, or textiles, or—I don’t know, whatever you want—but get to know it well, little by little, making space in your life for something you want to know about (that is not a geopolotical crisis).

Start a nature journal. I have been meaning to do this forever, and I am going to. My Pronking Year taught me that maybe I could learn how to draw. Anyway, keeping a nature journal helps maintain those habits of noticing and wondering and experiencing awe. Often, people note how a gratitude journal is good for mental health. Instead, I’m suggesting you jot down five things you notice every day in nature (whether or not you can draw them). We are nature, we live in nature, it is all around, no matter where we are. Jot it down.

Take a digital tour. Visit the website of an art museum and explore the pages they curate for their galleries. The access we have to art today would blow the mind of someone even 25 years ago. Bloomberg Connects also has gallery guides for over 1250 museums and historical homes.

Tell me, when did you last experience wonder or awe? How did you feel afterward? Do you have a wonder habit?

You might also be interested in my post at Brevity Blog, “How a Box in the Woods Taught Me to Write About Nature” or “Crossing the Stream” at Adanna Literary Journal, a piece I wrote about one of the weirdest paintings I’ve ever seen.

Related:

My wonder habit is running. I can find joy and awe in it anywhere. At dawn, at dusk, at night, on a hot summer day. Over mountains and through plains. And recently - endless miles on a quarter mile loop around my favorite burrito joint.